Berkshire Hathaway 1998 Annual Report Download - page 11

Download and view the complete annual report

Please find page 11 of the 1998 Berkshire Hathaway annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report.

10

The Economics of Property-Casualty Insurance

With the acquisition of General Re — and with GEICO’s business mush rooming — it becomes more important than ever

that you understand how to evaluate an insurance company. The key determinants are: (1) the amount of float that the

business generates; (2) its cost; and (3) most important of all, the long-term outlook for both of these factors.

To begin with, float is money we hold but don't own. In an insurance operation, float arises because premiums are

received before losses are paid, an interval that sometimes extends over many years. During that time, the insurer invests

the money. Typically, this pleasant activity carries with it a downside: The premiums that an insurer takes in usually

do not cover the losses and expenses it eventually must pay. That leaves it running an "underwriting loss," which is the

cost of float. An insurance business has value if its cost of float over time is less than the cost the company would

otherwise incur to obtain funds. But the business is a lemon if its cost of float is higher than market rates for money.

A caution is appropriate here: Because loss costs must be estimated, insurers have enormous latitude in figuring

their underwriting results, and that makes it very difficult for investors to calculate a company's true cost of float. Errors

of estimation, usually innocent but sometimes not, can be huge. The consequences of these miscalculations flow directly

into earnings. An experienced observer can usually detect large-scale errors in reserving, but the general public can

typically do no more than accept what's presented, and at times I have been amazed by the numbers that big-name

auditors have implicitly blessed. As for Berkshire, Charlie and I attempt to be conservative in presenting its underwriting

results to you, because we have found that virtually all surprises in insurance are unpleasant ones.

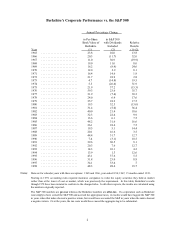

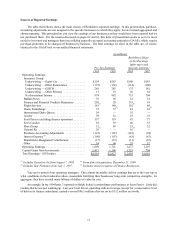

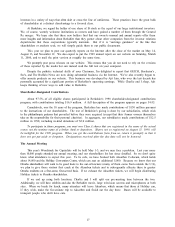

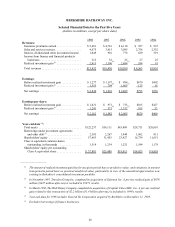

The table that follows shows the float generated by Berkshire’s insurance operations since we entered the business

32 years ago. The data are for every fifth year and also the last, which includes General Re’s huge float. For the table

we have calculated our float — which we generate in large amounts relative to our premium volume — by adding net

loss reserves, loss adjustment reserves, funds held under reinsurance assumed and unearned premium reserves, and then

subtracting agents balances, prepaid acquisition costs, prepaid taxes and deferred charges applicable to assumed

reinsurance. (Got that?)

Year Average Float

(in $ millions)

1967 17

1972 70

1977 139

1982 221

1987 1,267

1992 2,290

1997 7,093

1998 22,762 (yearend)

Impressive as the growth in our float has been — 25.4% compounded annually — what really counts is the cost

of this item. If that becomes too high, growth in float becomes a curse rather than a blessing.

At Berkshire, the news is all good: Our average cost over the 32 years has been well under zero. In aggregate, we

have posted a substantial underwriting profit, which means that we have been paid for holding a large and growing

amount of money. This is the best of all worlds. Indeed, though our net float is recorded on our balance sheet as a

liability, it has had more economic value to us than an equal amount of net worth would have had. As long as we can

continue to achieve an underwriting profit, float will continue to outrank net worth in value.

During the next few years, Berkshire’s growth in float may well be modest. The reinsurance market is soft, and

in this business, relationships change slowly. Therefore, General Re’s float — /3rds of our total — is unlikely to

2

increase significantly in the near term. We do expect, however, that our cost of float will remain very attractive compared

to that of other insurers.