Sennheiser 2012 Annual Report Download - page 7

Download and view the complete annual report

Please find page 7 of the 2012 Sennheiser annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report.

13

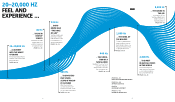

XX Hz 80 Hz

On a June day in 1986, the very foundations of Mexico

City’s Aztec Stadium were shaken. An extraordinary

atmosphere, an almost religious ecstasy – like those

many people feel as they are exposed to a great piece of art

– was felt by the some 114,600 viewers seated under the

gigantic dome. Argentina’s Diego Maradona had single-

handedly brought the score up to 2:0, pushing 50 meters

past the opposing team – dribbling past his competitors like

ninepins – to drive the ball into England’s goal. Years later,

his athletic feat was voted the goal of the century.

Argentine radio reporter Hugo Morales followed

Maradona’s magic march from the press box. He immedi-

ately knew that he would never be able to keep up with the

all-out attack by reporting in complete words, let alone sen-

tences. “Siempre Maradona ...,” is all he could get out and

these syllables have become almost as famous as the goal of

the century: “Genio! Genio! Genio! Ta! Ta! Ta! Goooooool!” By

translating Maradona’s fast twists into short blasts of

sound, without realizing it, Morales was anticipating sports

sonification, a method sports re-

searchers such as Prof. Alfred Effen-

berg of the University of Hanover are

using today to capture the sequence

of motions of swimmers and rowers.

Using synthesizers and computers,

they are able to construct an “acoustical fingerprint,” a

soundtrack of the motion. By employing this acoustical tool

during training, athletes can correct mistakes and improve

their technique.

Effenberg’s latest experiment is sound soccer, in

which the professor is conducting a study to establish

whether or not ear training is also applicable to soccer. The

Borussia Dortmund fan, who – despite having the same last

name – is not related to the former FC Bayern star, sought

out a competent partner. Cologne musicologist Manfred

Müller had already translated soccer players’ dribblings into

music for a radio show during the 2010 FIFA World Cup in

South Africa. Film composer Matthias Hornschuh assisted

him in translating the “Ta! Ta! Ta!” into beats and notes, turn-

ing sound soccer into a truly interdisciplinary project. “Good

teamwork is dependent on the players having a common

time base,” explains Effenberg. “We

know that synchronizing the timing of

more than one person is better con-

trolled using acoustical than visual sig-

nals, so we looked into whether a cer-

tain type of music and certain rhythm

could improve a team’s passing game.”

It’s no coincidence then that

football reporters transcribe football teams into music.

Dynamic soccer teams like Real Madrid and Dynamo Kyiv are

known as white ballet and red orchestra. Using tiki-taka to

describe the short quick passing game of the World and

European Champion Spain is also pure onomatopoeia.

Effenberg and his staff have three soccer teams

participating in their experiment. Not Real Madrid or FC Bay-

ern, but the youth and men’s team of FV Engers 07, and the

women’s team of Eintracht Wetzlar, both German associa-

tion football clubs. Sennheiser provided the technology. Prof.

Jürgen Peissig from the research department was immedi-

ately enthralled by sound soccer: “If the experiment suc-

ceeds, it could open up a completely new market,” and sees

a real potential for innovation. The project requires high

standards of quality because “ultimately, the complete mu-

sical spectrum from 20 to 20,000 Hz has to be transmitted

wirelessly to the players’ ears – the perfect situation for our

in-ear monitor systems.”

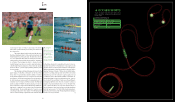

In sound soccer, directional antennas are installed

on the sidelines and each player wears a Sennheiser in-ear

sports headphone designed especially for joggers. Its sili-

cone earclips ensure a secure fit. In addition to soccer shoes

and shin guards, each test subject also wears a receiver on

his or her body. The mobile-phone-sized EK 300 IEM G3 is

attached to a belt around the hips. The trainers caution the

players not to battle too hard. Effenberg and his staff then

give the athletes instructions, but none of them know what

it is all about nor whether the other players are also listen-

ing to music. Five teams are randomly picked. At first, they

play against each other without listening to music, and then

with music. Müller and Hornschuh’s composition is a sonifi-

cation of the dribbling of South African national player Teko

Modise set to the rhythm of 140 bpm. Ball and ground con-

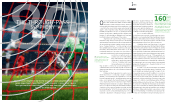

German sound engineers are on the trail of a winner’s rhythm. Their sound

soccer experiment shows that music can improve a soccer team’s game.

The right acoustical input drives a faster one-two pass – from the dance

floor to the winning goal.

SOUND SOCCER

e1. Cross, header, boom!

Bayern München striker Mario

Gómez shows how to set up

the perfect attack. Here, in

front of the goal.

BEATS PER MINUTE

160That’s the

minimum

beats per

minute

(bpm) of a drum or bass track – and

the beat of Maradona-successor Lio-

nel Messi’s dribble. Whereas rowing

eights might find 40 bpm too fast,

in classical music it’s considered

slow (lento). Sound soccer research-

ers play 140 bpm in players’ ears –

and improve their passing games.

12

THE THROUGH-PASS

SYMPHONY

80