Sennheiser 2012 Annual Report Download - page 5

Download and view the complete annual report

Please find page 5 of the 2012 Sennheiser annual report below. You can navigate through the pages in the report by either clicking on the pages listed below, or by using the keyword search tool below to find specific information within the annual report.

0908

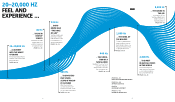

20–20,000 Hz

There are sounds that touch

the soul. Sounds that com-

fort, strengthen and raise

us up. A good sound has charis-

ma. Though “charis” literally

means “grace,” it also means

“beauty’s charm.” Finding the

perfect sound has become my

purpose in life – a journey that

has taken me into the heart of

sound. In order to set off on that

journey, however, I had to leave

music school and enter a school

for violinmaking. To move for-

ward, I studied physics. And to

get there, I dared the impossible – to create a sound that no

instrument in the world has ever produced. But my journey

has not yet come to an end.

Others may have finished their journeys. Such as the

great Italian violinmakers Antonio Stradivari and Joseph

Guarneri del Gesù. The secrets they took with them to the

grave are inimitable – even to this day. Their instruments

are not just works of art valued at millions of dollars – they

are being played to this day by the world’s greatest virtuosi.

But how is that possible? It’s a question I’ve been

asking myself since I was seven years old, when I was at-

tending a small music school in Swabia. Music is my life. We

played music at home on Sundays. I’ve

played in a chamber orchestra, a hard

rock band and in the pedestrian zone.

We even built our own tube amp. But

the rest of the time, I was at school, lis-

tening to the constant answers to

questions I had never asked. That’s

why I left the music school after the 10th grade and began

studying to be a luthier – a violinmaker. Driving me on was

a dream of building instruments with a better sound than

a Stradivarius and – should I not succeed – to find out why

it wasn’t possible.

Did the masters of the 18th century have some kind

of secret knowledge? Or was it the wood’s aging process

that gave their instruments the

kind of mature sound a young

instrument could never achieve?

The violin originated during one

of the most remarkable eras of

all times. For the great masters

of the Renaissance, combining

art and science was just a matter

of fact. It is unfathomable to think of such artistic works

being created without this special attention to detail and

feel for nature. It requires an environment of gifted em-

piricism and holistic intuition to design such highly opti-

mized acoustical systems. In the 19th century, however, the

art of violinmaking fell prey to the trade of the industrial

revolution.

The guild had sold its soul. But how would I manage

to reconnect to the art of sound? I first began by trying out

countless of the different recipes used to make traditional

varnishes. However, it soon became clear to me that the old

masters would have combined science without forfeiting art

– just as acoustician Helmut Müller taught me. A physics

teacher at my violinmaking school, he operated a research

laboratory at his acoustic consulting firm Müller-BBM. It was

in his laboratory that I was able to pursue the answers to all

the unresolved questions I had tortured him with for so

many years.

And then, a revelation: modal analysis. A method

used in aerospace technology. I was the first one to apply it

to the violin. At last, it was possible to actually see how the

violin vibrates. The bulbous breathing in the lowest natural

frequency – the Helmholtz resonance around 260 to 280 Hz.

The strong distortion of the lower corpus resonances, the

extensive motion of the plates and their two main reso-

nances 440 and 550 Hz, and their wide deviations around

35

ESSAY

e1. The master at work:

Schleske’s studio is located

in a nature reserve. When

he opens his window, he

can hear the sound of a

babbling brook.

e1. Historical scrolls and peg boxes: Our author

has been studying historical violins from the

18th century for decades. g2. Carving a violin:

The inspired sound researcher hews the tone-

wood himself. In the laboratory, he applies var-

nishes he has prepared according to traditional

recipes.

MY PURSUIT OF THE

PERFECT SOUND

From the lowest depths to the highest heights: Music envelops the complete

spectrum of sound audible to the human ear: 20–20,000 Hz. But which of

these resonances are able to touch our souls? German Martin Schleske, one

of the best luthiers in the world, is in hot pursuit of the answer. In this essay,

he describes his unique journey into the heart of sound.